In Conversation with Dominic Ansah-Asare: Part 2

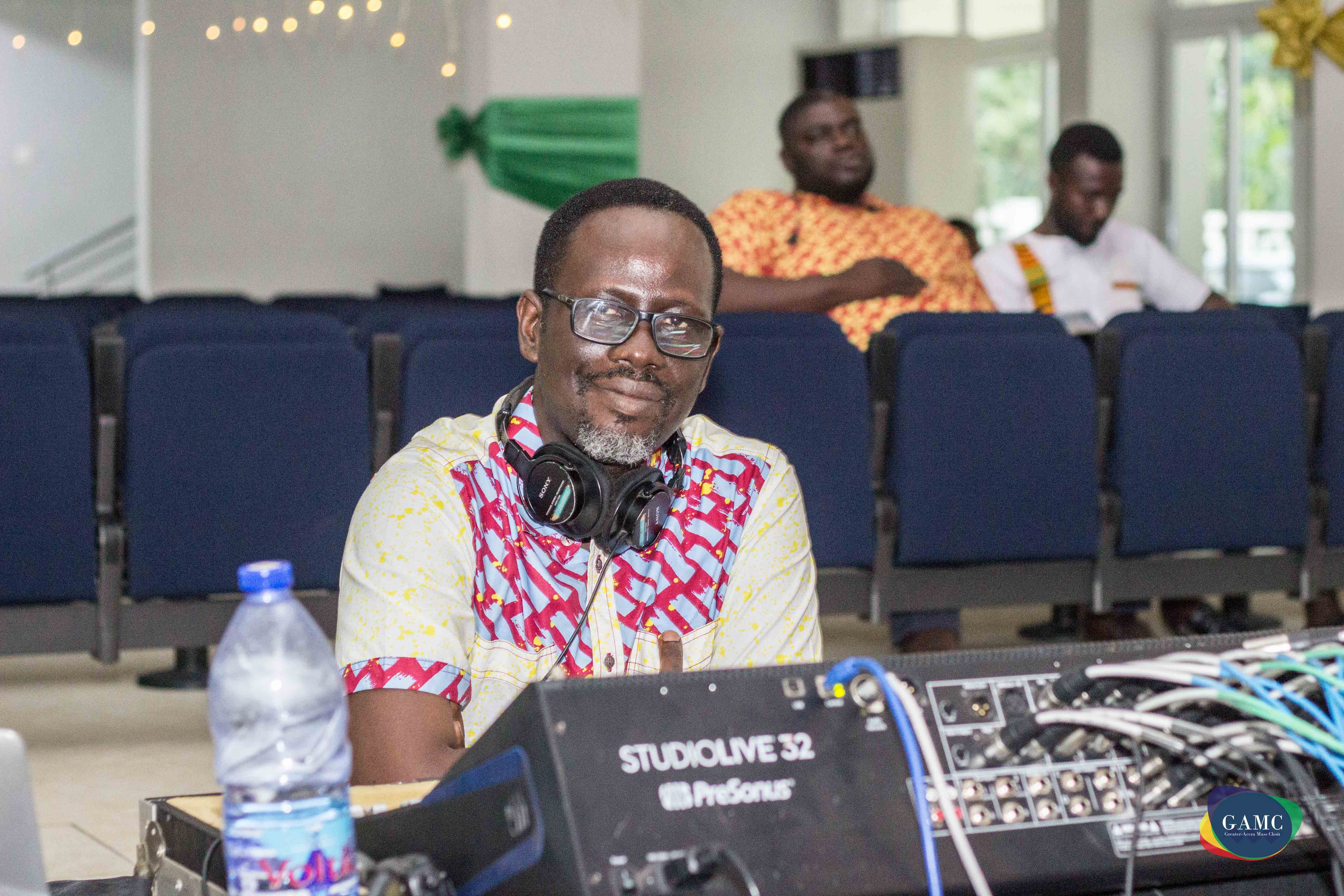

As one of the most popular personalities in the choral and classical music space, and the world of Ghanaian sound engineering, Dominic Ansah-Asare needs very little introduction.

His outfit, MIDO Productions, has been the brain behind the sound of some of the country’s most successful choirs, including the likes of Harmonious Chorale and One Voice Choir. As such, his workmanship has been heard by thousands around the world thousands of times. Yet, not many have heard from the man himself.

In this second part of our conversation with Dominic, we delve into the world of MIDO Productions and the impact he has made in Ghana since turning his attention to sound engineering.

This interview was originally conducted in January 2020.

CMG:Tell us about your entry into the Ghanaian sound engineering market.

Dominic: A number of things came together to force my move to Accra. A good friend told me to stop wasting my time feeding fowls in the Volta Region, because there was a lot of business in music. Family circumstances also compelled me to consider relocating to the capital. I arrived in 2000 - in time to join Dr. Ross’ British Council workshop.

In my earliest years, I met several prominent engineers, most of whom I looked up to. I had had interactions with the likes of Zap Mallet, even before he became a sound engineer. I started out helping choirs, small groups and individual artists record their music. When I was ready to do business, I approached the likes of TVO Lamptey, the engineer behind the gospel choir Joyful Way Incorporated, and Jude Lomotey, to discuss my desire.

CMG:In which year did you start Mido Productions?

Dominic: January 2001.

CMG: Tell us about the first years of your company

Dominic: I started out in the classical/choral genres, before branching into more contemporary work. One thing that compelled me to commit to sound engineering full-time was the number of jobs I got. One such assignment was for Ghana Telecom, when they were introducing their One Touch product. I was behind the jingle. I also worked with Brew Riverson and Grace Ashy, on their albums, as well as the jingles aired when the redenominated cedi notes were being introduced. I had other jobs from within the African subregion.

One interesting experience in my formative years was with some hiplife artistes. I got the job on a Sunday, and left church and headed straight to my studio, still dressed in my black trousers and tie: typical choirmaster attire. When my clients first saw me, they thought I couldn’t deliver.

CMG: What were some of the highlights of those years?

Dominic: I had a lot of high-profile experiences in business. Even when I was a judge on TV3 Mentor, it never once got into my head to consider myself a star. Once, I had to go to Makola market to get something for my studio. That was at the height of the program. I immediately found myself surrounded by fans who recognised me from the show. That was when I first experienced the impact of fandom. I was confused. But I never let that experience get into my head. I never changed my dressing or my lifestyle.

Most of my work has been in the choral scene. Mido has recorded over 3000 concerts. I believe my work has contributed to the success of some of the big choirs in the country.

CMG: Can you describe some of your greatest challenges, and how you overcome them?

Dominic: I’ve been through a lot. I faced a lot of difficulty in starting my business - just as every young person does. I could sit for months without having anything to record. But, thanks to ideas about vertical and horizontal integration I gathered from my Economics studies, I could use my equipment - for instance, my keyboard - for teaching when it wasn’t being used for recording. I could transition from studio recording to providing PA systems at external venues, to out-of-studio recordings.

I’ve also messed up some big opportunities while I was learning. I used those instances to learn from my mistakes. Some of these lessons helped me provide value to other high profile clients. By vowing not to repeat my mistakes, other people have come to believe in my dream. Clients you have messed up may not give you another chance, but new clients who benefit from those learnings will stay. That is why our clients stay with us.

CMG: What lengths have you gone to improve your craft?

Dominic: At one point, I decided to cement my knowledge in sound engineering by furthering my studies. I took an online course with Berklee College in the United States. It included rigorous studies in critical listening and many other things. I ended up with a certificate as a live sound specialist.

I’ve looked up to people such as Bruce Swedien (the Grammy Award winner who worked on Michael Jackson’s Thriller) and Quincy Jones. I’ve read them in and out, to learn what they did to create the sounds they are noted for.

CMG: Give us insight into your non-Ghanaian collaborations.

Dominic: I’ve worked with a Mormon choir that collaborated with Harmonious Chorale. I also worked with Richard Elliot and Randall Kempton from The Tabernacle Choir, during their collaboration with Celestial Evangel Choir and Gramophone Chorus. I’ve had concerts in Togo, Nigeria, Benin and in South Africa, when Harmonious Chorale competed (and won honours) at the World Choir Games. Although it was the choir that won those honours, there were things I did to ensure the production was successful.

I must add that, some choirmasters think it is the sound engineer’s job to make their choirs sound great, but that is not the case. When you get on the international stage, you will realise things are different.

CMG: When did you start working with the National Symphony Orchestra?

Dominic: I’ve been working with them consistently for three years, primarily because of the Tierra Pura concerts. Earlier on, I did one-off jobs for them, for instance at One Voice Choir’s Awake and Build Africa. They are not the only orchestra I’ve worked with. I was called to oversee the Accra Symphony Orchestra’s sound on the day of their launch, to ensure they had the best output.

CMG: How does that work?

Dominic: When you study critical listening, you will appreciate how various orchestral instruments are supposed to resonate. As a sound engineer, your ear is trained to be able to hear well. That’s about it. The genre of the production is dictated (and directed) by the producer. As the sound engineer, your job is to listen to the producer and ensure the various frequencies are all “breathing well”.

The orchestral sound comes naturally to me. I know the instruments. I am very familiar with their sound, so I know what I must go for.

CMG: Can you share some thoughts about sound engineering in Ghana?

Dominic: Sometimes we confuse the roles of the engineer and the producer. We try to take the producer out. We expect the sound engineer to know how to “play something”, but that’s wrong. As an engineer, what matters is your ear, and the physics of sound, and how you interplay the sound within the performance space. And you must learn to listen to your producer, who knows the market and trends within the genre of music you’re working in.

The quality of sound engineering in Ghana is good. I think sometimes people don’t want to follow standards - they go in for too much energy. Choral Music usually allows a wide dynamic range in the choir’s output. James Armaah’s conducting brings that out, and I try to faithfully capture it. Other sound engineers don’t understand this. They treat the genre like contemporary music, which can have dynamic variance of only about five decibels. In choral music, you can have a variance of up to 30-35 decibels in the same song.

For me, the conductor’s intention is what I try to master. If a verse of a song is piano, I will not boost it. I don’t think of it as “low”: I think of it as intentional. Besides these few issues, I think the quality of sound engineering is generally good.

CMG: What are some of the learnings from your life as a farmer that directly influenced the things you do at Mido?

Dominic: When you are managing agriculture, the fact that your birds are being attacked by a particular disease doesn’t require you to buy all the vaccines in the world. It is a lesson you take into business: when costing for profitability, you must create a profit and loss sheet to model your business. The Economics I learned in agriculture is purely what you need to run a business. I don’t regret my time in agriculture. In fact, it has helped me.

CMG: What makes you successful?

Dominic: Prayer. Determination. I went to work in the Ewe land and someone asked me: “Director, where do you go for your juju? I want some.” I owe it to God. My Presbyterian background inspires me to approach everything with discipline as a hallmark.

In the sound engineering world, Mido is hardly late. Our brand is to be ready an hour or two before the time you give us. I had to start charging people for lying to us, because some people think all Ghanaians are not serious with time. They tell us their program will start at 4pm, when they know it will start at 6pm. This caused us to start charging for the time we spent waiting.

The kind of home I grew up in also had an influence. My father didn’t have anyone before him study music: he was largely self-taught. That spirit is something I imbibed. I like to read. I never use a mixing board without learning absolutely everything I can about it. I am not going to learn at your event. And this is something I enforce at my company. None of my employees will get to use a mixer until they know everything about it. These are some of the things we do to make our work exceptional.

Dominic’s influence within the sound engineering industry in Ghana, and the choral and classical space is undeniable. From his rise as a teacher-trainee at the British Council at the start of the century, Mido Productions has helped raise many of the popular engineering talents active today.

Besides his production work, the Music Solution School exists as a testament to Mr. Ansah-Asare’s commitment to music outside of his technological and commercial interest, and to his belief that local musical talent must be developed to make it globally competitive.