Is the Government doing Enough for Art Music?

Earlier this week Ghana’s senior male national team, for many the pinnacle of our country’s sporting pride, failed to progress to the Quarter Finals of the 2019 AFCON tournament. The team also made history on Monday night when, for the first time they were knocked out by Tunisia. This follows their last attempt to qualify for the 2018 FIFA World Cup in Russia - an endeavour that raised, and then dashed the hopes of a nation.

Late last year the Black Queens, Ghana’s senior female national team did not make it past the group stage of the Women’s AFCON which they had the advantage of hosting. These two examples are just the latest in a long string of disappointments soccer fans - and the general populace - may have already become used to, with regards to our national pride in the sports arena.

Soccer is of immense national importance: it stands as the country’s most celebrated sport and enjoys heavy investment from the government and associated agencies. Yet for all the money poured into it, there doesn’t seem to be much in terms of the positive emotional returns.

Sporting success isn’t the only avenue for inspiring national pride. The arts and cultural scenes of any country are easily a source of strong positive national sentiment and identity.

Just as sports and the arts are usually a matter of individual dedication and excellence, and success in those fields usually benefit those few directly involved, the social context of these activities translates individual achievements into communal successes celebrated even by those who only pay casual attention to those areas. The recent achievements of Isaac Dogbe had a profound effect on the nation’s identity as one of formidable boxers - a tradition cemented by Azuma Nelson in the 1980s.

The case for state sponsorship of sports rests on the fact of the shared success individual and team talents reap for the country. And this is realised in the amount of interest and financial support the government has for soccer. Rather than assume the cynical opinion that regards government sponsorship as using taxpayers’ money to pay wealthy celebrities to kick rubber balls in exotic stadia, we generally understand that the country benefits directly from investment in the success of its national teams. The same can be said of boxing.

Such patronage is common elsewhere, and this is not restricted to sporting disciplines. Perhaps the most stellar example is the film industry of the US, dominated by Hollywood. The success of the American film industry is a story of how effective (and sometimes clandestine) state partnership can transform a novelty technology into one of the most influential and valuable in the world. It also underscores another benefit a vibrant cultural export can be on the world stage: promoting a positive cultural image of one’s country is an effective propaganda tool, and the most powerful governments in the world invest billions to make sure these cultural assets are preserved, improved and exported the world over.

Our own government hasn’t lost sight of the importance of sustaining a vibrant artistic ecosystem: successive administrations since the Rawlings era have had tourism and other culturally-focused ministries with the purpose of representing the creative society at the highest levels of power. And these ministries have hardly been idle! The artistic space in the country is large, and there are a lot of hands waiting to be assisted to improve their own neck of the woods.

Those of us in the art music industry aren’t left out of the conversation around funding for our creative arts. There are a number of strong arguments to be made around the state of government support of art music, both for its own sake and in the larger context of the pursuit of national honours.

Last year, while our national soccer teams were failing to live up to our expectations, a group of young Ghanaian men and women, supported for the most part by private donors, shocked the world of choral music by emerging with top honours at the 2018 World Choir Games, an international competitive singing event featuring some of the best choirs from across the world. It quite literally was a musical world cup, and a team representing the country made waves (in the country’s name) and put the nation on the map. Harmonious Chorale may have won those accolades for itself, and its choristers. However, the fame still rubs off on the nation as a whole, especially those involved in the type of music the choir is famous for.

Anyone looking for something about Ghana to smile about last year could point to the four gold medals picked up by the first Ghanaian choir to participate in this competition as an achievement worth celebrating.

Stepping back from the single success of this one ensemble, Ghanaian choral music as it is practiced today preserves the legacy of one of the greatest contributors to the world of ethnomusicology. The intellectual giant that is Nketia in the musical world has inspired at least three generations of Ghanaian musicians who have given the world an authentic musical expression worthy of global celebration.

This is not a fatuous claim: other African countries, such as South Africa, have so successfully marketed their brand of choral music that their flavour of music is recognized globally as belonging to them.

The same could be said of Ghanaian choral music, were it to survive the next half-century. Anyone who doubts this cultural asset promoted by heroes such as Ephraim Amu and his contemporaries is in danger of dying out has not observed the state of church music in Ghana, and its tendency towards the hip, Western and “popular” taste. It would seem that Ghanaian choral music should be treated with as much respect as the Adinkra symbols are.

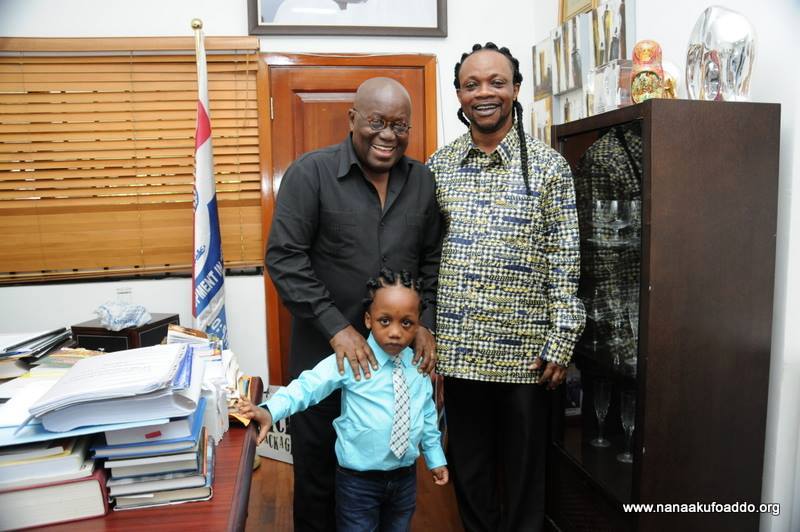

There are strong arguments for the increased promotion of Ghanaian art music by the government, and some of the brightest minds in choral music have expressed their dissatisfaction at the status quo. James Varrick Armaah - the enterprising musician and choir director who led his choir to the earlier referenced achievements - has reasoned that “our abilities and interests can never be the same, so any country that is serious about building its citizens up should promote all energies of its people, rather than focus on what looks popular.”

It is not uncommon to hear people within the space complain about issues minor and major, that add to the clamour for state support of these arts. Common scenarios cited include the strength of our Ghana’s Symphony Orchestra (perhaps the most explicit symbol of the state of serious music with respect to our government’s interests) and the lack of visibility of the industry in national conversations around entertainment, especially music awards.

But do these complaints hold up to scrutiny?

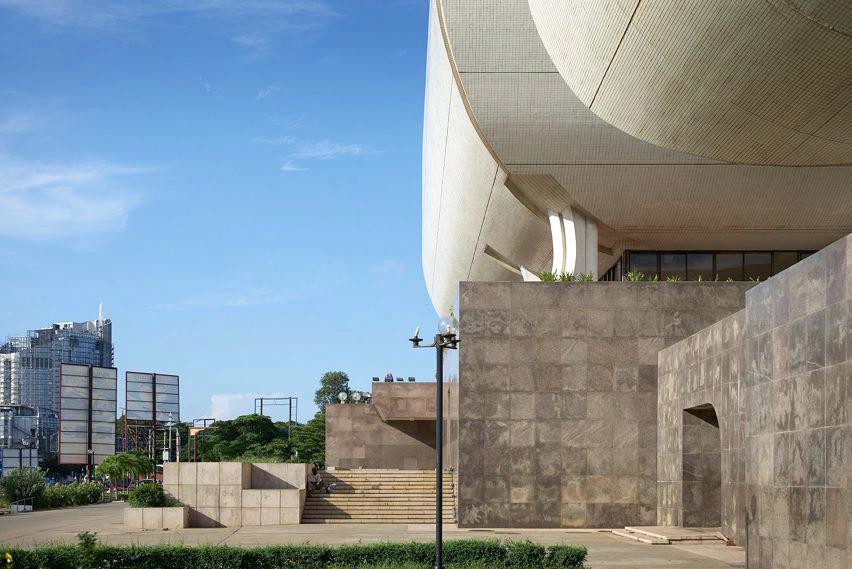

The existence of the National Symphony Orchestra, despite whatever opinions some may have about its current state, is evidence that previous administrations have not been idle in their promotion of art music. To put this in context, this is one of several institutions that has survived various changes in government, legitimate and violent. The controversial first president, in founding the orchestra, intended it to promote both Western and Ghanaian art music. And to a large extent, it has done just that. With the help of the Chinese government, the National Theatre was built as a home for the country’s arts. And, to this day, the iconic building exists as a national symbol of public interest in this sector.

Two public universities, the Universities of Ghana, Cape Coast and the University of Education, Winneba, have grown to become breeding grounds for the best of Ghanaian musical scholarship. These institutions have worked to preserve some of the most important research work of past academics, and have been associated with the most influential contemporary performers. National broadcasters such as Uniiq FM (owned by the GBC) have kept classical music and Ghanaian choral music on air for about fifteen years.

Our industry is one of the few to be given the honour of having one of its representatives featured on our currency. No footballer is yet to grace the cedi.

Recent administrations, it seems, have noticed some of the fine work of our choirs, and have given them pride of place in public events. Most recently, a choir was among the groups that performed at the Independence Day celebrations held in Tamale. This suggests to us that our leaders have been paying attention to our genre of music and, perhaps, they show more interest in it than it would naturally generate, since this music tends not to be “popular” in character.

Interestingly, there are equally good points to be made against the necessity of the state dedicating more public funds to the industry. Considering the matter broadly, government intervention in the arts can increase the amount of censorship and propagandizing, both of which reduce the core value of any artistic endeavour: authentic expression. The earlier example of the success of American cinema we cited is not without its caveats. Hollywood was largely built on the backs of enterprising private businessmen who took the risk, and reaped enormous rewards from their investment.

US government partnership does not mimic the patronage some artists look up to: the power, it seems, lies with the industry, whose commercial strength and social influence has made it indispensable to the government when it needs to shape public opinion.

Even with that more favourable position, journalists have raised questions about how much government involvement is bad for the credibility of the oldest, most successful movie industry.

We’ve seen a similar dance play out in the country, with popular music benefiting from government/political patronage, to good and bad effect. Pop musicians have campaigned for political parties, or used their image to push the national agenda. Some artists have even gone on to take up roles in government.

Ghana’s hosting of the 2018 AFRIMA (All Africa Music Awards) drew criticism from some quarters, who weren’t excited about the 4.5 million USD price tag of the event over three years.

Just last month, Ebo Whyte, the playwright who may have single-handedly transformed the landscape of his industry in recent years, came out strongly against the notion of “waiting for government intervention” in the arts. He is quoted as saying that artists will continue to be disappointed “until [they] work hard and attain the heights that will ensure government cannot do without the sector and would have no option than support it.”

He seems to be following his own playbook. For ten years, his production company, Roverman Productions, has grown to become a cultural force in the contemporary arts in Ghana, taking their shows on tour in several cities within the country.

Other players in the choral/classical music space seem to have understood this, and are working on commercializing their work. Most notable of these efforts at bootstrapping the industry has been the “Gh Youth Choir Choral Festival & Awards”, the industry’s largest awards show which is in its third year.

Perhaps it is only a matter of time before the Ghanaian government finds art music as indispensable as the competing popular variants. The state has already made advances in institutionalizing the promotion of our cultural heritage with the creation of the National Folklore Board to safeguard these very things we speak of.

Whereas the economics of attention currently do not favour this industry, such that it remains a struggle to justify more public expenditure in art music, it is still worth noting that if millions of public funds can be spent on other similar pursuits, a little help can go a long way.